India — December 2025

I love trains. I love watching the passing scenery through the window and letting my thoughts wander. I love the mix of passengers and imagining where there might have come from and where they might be headed. Combined with my passion for reading, it’s no surprise that I’m a big fan of books like “The Great Railway Bazaar” by Paul Theroux. That specific travelogue is probably the reason why I’ve been dreaming of (& romantizing) travelling across India by train for so long. I made the dream come true in a small way with my trip to Kashmir (read about this here: New Delhi-Jammu). A second attempt during my first visit to South Asia failed tragically (read about that here: New Delhi-Agra). Now I’m back in India and catching more trains. Read on as I explain all I learned about the great railway country so far.

Act 1: buying a ticket, waitlists and RAC.

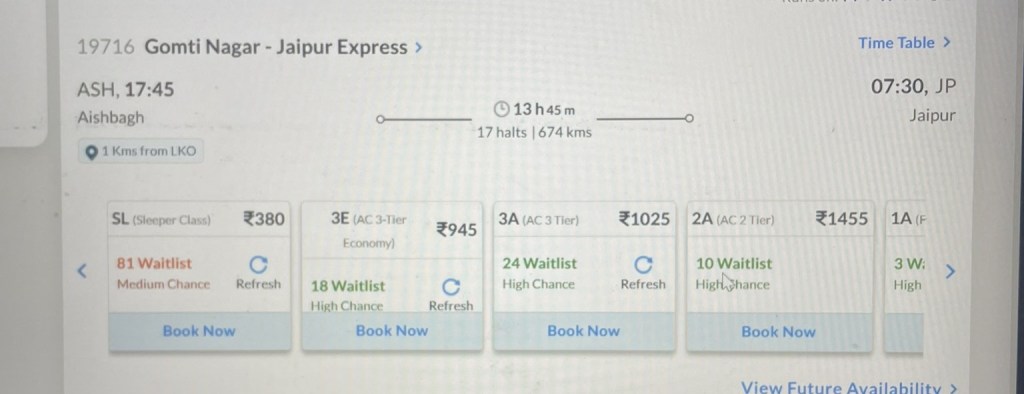

Usually I like to buy my public transport ticket in person at the ticket office of the provider. But nowadays, the sales are mostly done online. One advantage is that the haggling and cheating are minimized (yet never zero). A dissadvantage is the somewhat complicated system. You first create an account on the IRCTC website. For this you require an Indian phone number. You then find the connection you’re looking for. A heads up: many large cities have multiple stations. For my journey from Lucknow to Jaipur for example, I boarded at “Aishbagh Junction” and the arrival station in Mumbai from Udaipur was “Bandra Terminus”. Once you find a train you like, you will see a number of different available categories. Below the category number, the website states the available seats. If the number is black, there are still confirmed seats available. Tho in my experience (travelling during peak season in December) it is much more likely that the number is red and preceeded by “WL”, which stands for waitlist.

Sometimes the waitlist for a specific category may be as high as 80+, but as long as there is a number, you can still buy a ticket. Only if it says “REGRET”, the tickets are fully sold out. How exactly the system works is still a mistery to me (most Indian travellers too), but some how for both my journey from Lucknow to Jaipur and Udaipur to Mumbai, the waitlist cleared by early afternoon on the departure day. For the first trip I got a RAC notice, followed by a confirmed berth. For the second journey tho, my status remained at RAC. This status allows you to ride the train, but there will likely be another passenger with the exact same seat number for the whole journey or part of it and you need to share the bed. This is what happened during my trip to Mumbai: The train is already waiting for me when I arrive at Udaipur station. I make my bed on the assigned lower side bunk in the 3E car and sit down. By the time the train pulls out of the station (only 5 mins late) no other passenger claims by seat.

However, 2 stops later, a Rajasthani man shoves his confirmation in my face. I explain that we have the same RAC seat assigned and have to check with the train conductor if there are any free beds. We chat for a while and when there is no sign of the conductor after 20 minutes or so, the guy offers to temporarily take an empty middle berth, so I can sleep properly. I gladly accept and quickly doze off. 3 hours later, I wake up to the man standing in the aisle, his temporary bed taken by the righteous owner. He tells me that the train conductor has been looking for other options, but there are no other beds. Still sleepy, I finally agree to share the bed for the rest of the ride and we sit on opposite ends adjusting our legs every once in a while into a somewhat comfortable position. Definitely not my most restful sleeper train experience, but at least we arrive in Mumbai on time – which is not a given in India at all. More about that in Act 3, but first lets talk about the train stations.

Act 2: the stations.

They are often huge and not very centrally located. As mentioned before, there are usually multiple stations in 1 city – all with different names. Do reference Google Maps before booking. There are countless departures every day and tracks are therefore used by many different trains, reaching from local to super express. I usually check the number on the main sign in the station hall, and double check the accuracy of the information by asking multiple people who are waiting on the same track for their destination. This is the best way to avoid waiting anxiously, cause the tracks don‘t have any signs saying which train will be leaving at what time. There is also no information about where which car will be located. So allow ample time before departue to possibly walk along 10 or 15 cars till you reach yours. And then there are the other passengers: trains are often packed, so expect a lot of people hanging. Some may be sitting on the floor, some buy snacks at the platform vendors, and all of them are chatting. Just like most other places in India, it’s noisy and the information shared mostly in Hindi across bad quality speakers is indecipherable.

Act 3: the delays.

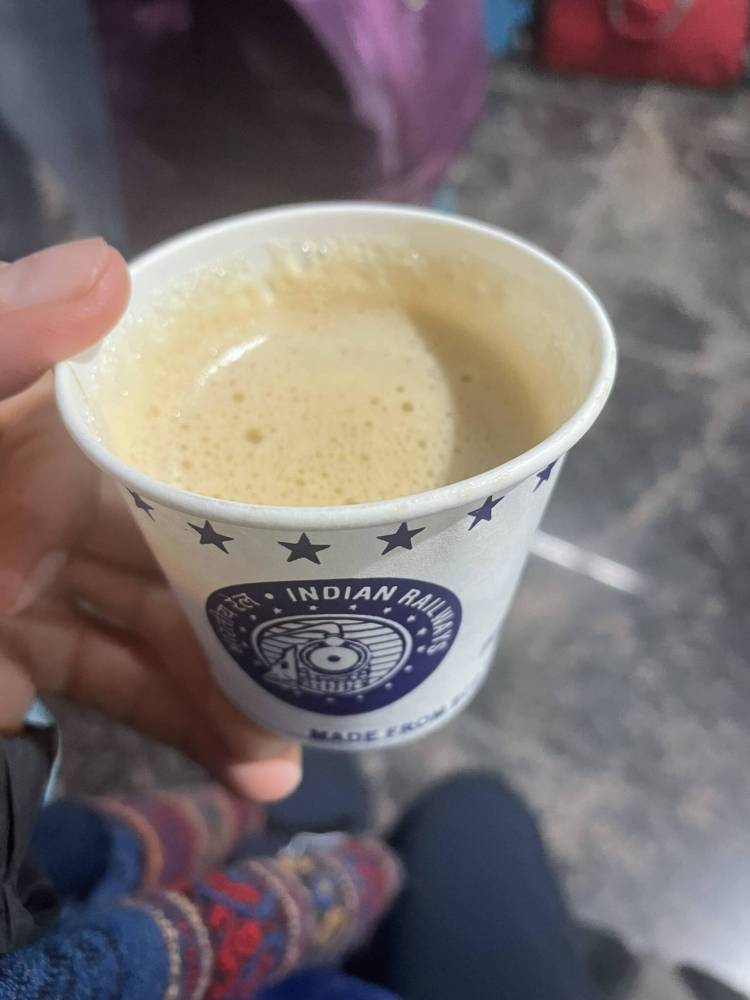

First up: 2 hours is considered average delay. I’ve heard horror stories from people who were stuck on a train for 35+ hours. Reasons are various. Someone told me that there are few lines across the country which are considered important, so trains on all other lines have to give way to those important ones. Another common reason for delays are technical issues. But how do you know if your train is delayed? The signboard at the main station hall is not always helpful. So far the best source of information for me has been the internet. By googling the train number + “train status” I reached https://www.railyatri.in/. The timeliness of the information varies, but for the more common routes it was quite ok. Finally, let’s talk real numbers. During my first journey from Delhi to Jammu the train’s departure was initally only slightly delayed, but the final arrival time was 4 hours late. In Lucknow I waited a whopping 5 hours for my train to arrive. The best thing to do in that case: drink chai and chat with strangers. Once it pulled into the station, a few people who were waiting with me have already given up and gone home. From when I boarded to the actual departure it took another hour or so. The final arrival in Jaipur was 8 hours past the scheduled time.

Act 4: the trains: beds, lavatory, food and people.

On the express long distance trains categories usually reach from General and seater car to Economy 3 Tier (3E), AC 3 Tier (3A), AC 2 Tier (2A) and AC First Class (1A) sleepers. Given the long distances, I always bought tickets for sleeper cars. Economy and General cars are fan only. That was fine during the trains I took in December, but judging from my Platzkart ride in Kazakhstan in August 2023, I wouldn’t recommend in summer. The numbers indicate the number of the bunks in each compartment. Eg. in AC 3 you have 3 beds above each other and in AC 2 only 2. Additionally, there are 2 beds above each other located sideways on the other side of the aisle. In the 2nd class cars, there are curtains that can be drawn between beds and aisle, which gives some more privacy. In the 3rd class cars there is no such thing as privacy. Another difference is that lower class cars have fewer power sockets. There are toilets onboard the train, with the option of squatting and western style (the latter being much more frequented and the former providing a challenge when the train is running). As usual, the cleanliness varies, there is no toilet paper and rarely running water.

What can be counted on tho is food: sometimes it is included in the ticket (on the journey from Delhi to Jammu I had delicious Dal Makhani). Otherwise you can order from delivery apps like Zomato or buy on platform at stops, from vendors getting on (incl chai!). Finally, what many people worry about are safety and other passengers. I’m happy to reports that so far, I haven’t had any unpleasant experiences. Other passengers (often families & generally older crowd) have always been respectful and happy to help when I asked for advice. The only minor inconvenience, which is unavoidable in India, is the noise: there is always someone on the phone, watching movies, playing music without earphones, etc. The noise level increases even more as the train approaches the final destination. About 1 hour before everyone gets off, people start to get ready, luggage is hauled from storage and you may encounter Hijras* offering blessings against a donation. You’ve reached the end of my report on how to travel by train in India. If you want to know more about India’s third gender, read on.

Bonus Act: Hijras.

You may wonder why I’m including a discourse about India’s Hijra community in this train tale. On Indian trains, encounters with Hijras—often moving through carriages offering blessings—are not random acts of begging but a continuation of a much older tradition adapted to modern life. Hijras are a recognized third-gender community in South Asia with a history stretching back over 2,000 years, rooted as much in culture and religion as in gender identity. Traditionally believed to hold spiritual power connected to fertility, marriage, and prosperity, Hijras have long been invited to perform badhai, ritual blessings for newborns and newlyweds, a role reinforced by Hindu mythology and devotion to deities such as Bahuchara Mata. Giving money in this context was meant to receive blessings or goodwill, not simply to offer charity. Over time, social change, urbanization, and exclusion from many forms of formal employment led Hijras to adapt these traditions to new settings. Trains—public, crowded, and constantly in motion—became a natural space where this age-old role could continue in modern India. For many Hijras, blessing passengers on trains remains one of the few culturally recognized livelihoods available to them, connecting everyday travel with a living tradition that blends history, spirituality, and resilience.