India – January 2026

Straight out of “Cobalt Blue”: an Indian movie set in Fort Kochi in 1996. The plot reminds of “Call me by your name”, with a brother and sister both falling in love with the paying guest moving into their family home. The movie does a great job at showing the stark differences between the traditional Hindu family life the parents lead and the younger generations alternative paths. The secret, queer relationship, is the centre point of the story. But there’s also the strong, feminist sister creating tension and the torn love interest who’s an artist in charge of transforming an old warehouse into a gallery. And this brings us to the present moment: my visit of the Kochi Muziris Biennale. Where art works are displayed at just that type of warehouse turned gallery spaces.

The Kochi Muziris Biennale spreads across Fort Kochi through buildings that once had very different purposes. A few that I visited include Aspinwall House, which used to be a large colonial spice warehouse complex, sitting right by the water, with wide courtyards, thick walls, and long corridors that now guide visitors from one artwork to the next. Pepper House was originally used to store and trade pepper, and it still feels smaller and more contained, with rooms that make you slow down and spend more time with each piece. Anand Warehouse stays close to its industrial roots, with high ceilings, exposed beams, and rough floors, making the idea of a warehouse turned gallery feel very literal. Mocha Art Café sits inside a restored heritage building and works as a break in between exhibitions — a place to sit, cool down, and process everything you’ve just seen. OED Gallery, more modern in structure, feels sharper and more political, with clean lines and focused lighting that put the works front and centre.

Another overlapping point between the movie Cobalt Blue and the Biennale is the presence of the queer community. Be it in artist identities, art pieces or visitors, the LGBTQ+ community is visible in many ways, which is not often the case in India – or Asia in general. At Pepper House is even a improv dance/theater performance by a lesbian couple running when I stop by there. Let’s have a look at some more artists and collectives that stood out for me: Smitha M. Babu’s Pakkalam series captivated with its richly textured watercolours that transcend the transparency of the medium to evoke the rhythms of everyday labour and community life in Kerala, blending memory and performance into each frame. Also set in Aspinwall House are the inclusion of historic yet timeless works by Lionel Wendt. The pioneering Sri Lankan photographer and modernist brought a quietly powerful exploration of the body, gesture, and presence through vintage portrait prints.

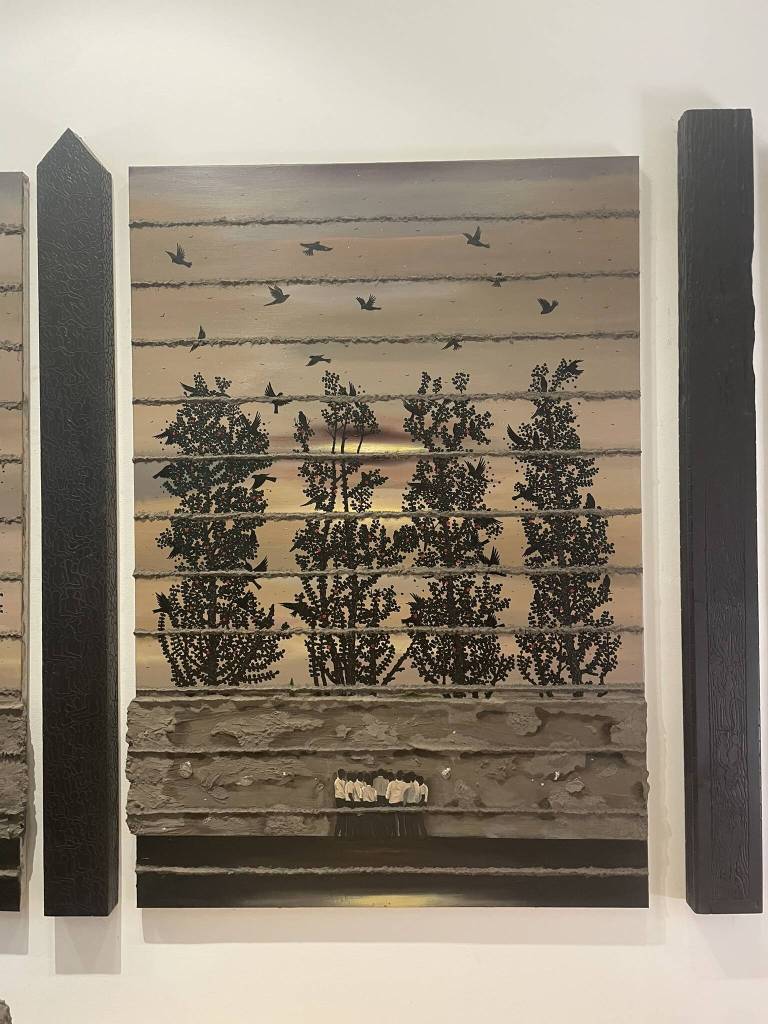

Abul Hisham’s practice infused the exhibition with mythological and psychological narratives, his pieces acting as portals into rich symbolic landscapes that linger long after viewing. I was also drawn to Zarina Muhammad’s contemplative installation, which carved out a sanctuary-like space for reflection and participatory ritual, inviting audiences to slow down and attune to the environment around them. The Panjeri Artists’ Union Bangalore brought a powerful collective voice, their collaborative practice weaving histories of place, pattern, and cultural exchange into installation that felt both grounded and expansive. Lakshmi Madhavan’s Looming Bodies arrestingly articulated the interplay of human bodies and the abstract. Taking the focus away from handloom works to their makers. Devika Sundar’s work stayed with me too. Her fluid, organic explorations of the body in flux, informed by medical imaging and intuitive mark-making, offered a poetic meditation on embodiment and experience.

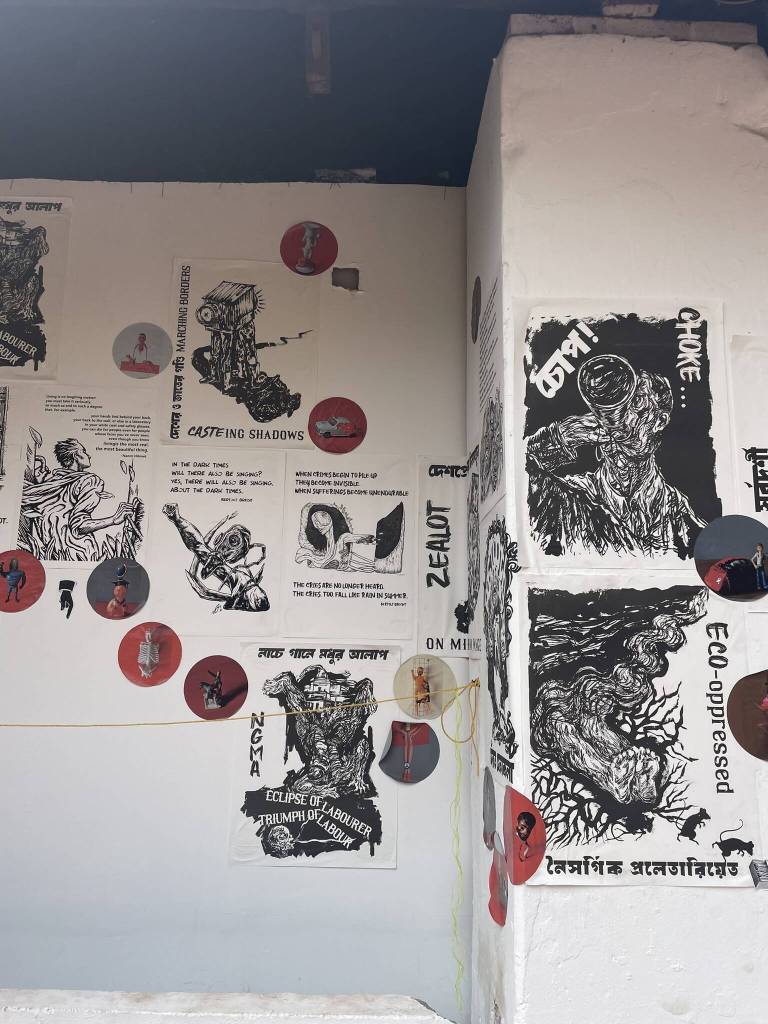

Throughout the OED Gallery’s spaces, the political artwork (from incisive commentary on labour, power, governance, and collective memory) added another layer to the Biennale’s broader objective. Those pieces left a lasting impression that art can not only reflect but also spark conversations about the world we live in. Discussing politics openly like that seems to be quiet normal in Kerala. At the hostel where I stayed in Fort Kochi I heard someone say “here we are the good kinda communists”, refering to the current communist party running Kerala. And in Cobalt Blue, communism and student protests come up in side plots. A big reason communism took root in Kerala was the state’s social structure before independence. Society was deeply hierarchical, shaped by caste oppression, feudal land relations, and exploitative labour systems—especially in agriculture and coir, cashew, and plantation work.

Left movements grew out of trade unions, peasant struggles, and anti-caste reform movements, often overlapping with early social reformers who pushed for education, dignity, and rights for marginalized communities. Which is likely the reason Kerala is the state with the highest literacy rate and health standard. Culturally, left politics deeply shaped Kerala’s art, literature, theatre, cinema, and public discourse. Writers, filmmakers, and visual artists often engaged with themes of labour, class, gender, and resistance—something you can still feel today, including at spaces like the Kochi-Muziris Biennale. The political consciousness here isn’t just about elections; it’s woven into everyday conversations and creative practices. All in all, I’d say a visit of the Biennale should be on anyone’s itinerary who’s coming to Kochi during this period. And needless to say, Fort Kochi is worth a stop any time of the year anyway!