India – January 2026

Forty minutes. That’s all it takes from stepping off the plane in Port Blair to boarding the government ferry headed for Havelock Island. And upon arriving at my final destination 2 hours later, the island vibes continue. 5 minutes into my walk towards Govind Nagar in the midday sun, a dive shop employee heading home offers me a ride. I arrive at Classic Hostel and run by Goldie and his family. The small guesthouse is tucked away in the jungle and features 1 private room, 1 five-bed dorm, a large common area and kitchen. It’s almost always full and I can easily see why. Indian and international guests flow in and out, with the shared bond being diving. And that’s why I’m here too: I head to Scubalov to check the dive schedule for tomorrow, but they want me to sign up to a refesher course first. So I end up joining nearby DiveIndia instead. Great energy, lots of women divers, a perfect fit.

The alarm rings early, but the sun is already up by the time I’m spreading peanut butter on toast at 5.50am — a reminder that India runs on one timezone, even though it’s 1300 km to Chennai on the mainland. By 6.15am we’re geared up and walking to the boat, joined by a few open water course trainees. Once on the boat, we’re heading out to The Wall, where an enormous octopus waiting for us as soon as we reach the bottom. The surface interval blurs into samosas and sharp, sweet chai, and soon we’re back in for dive number two at The Lighthouse; I’m skeptical when Nidhin mentions “disco clams,” but the moment I see their bright red shells and the mouth pulsing with blue current, I’m sold. Back on land, I’m having a delicous Thali lunch with roommate Sanjana, followed by fresh coconuts cracked open straight from the garden. In the evening, I head to the vegetable market for a quick grocery run to cook for the first time in months.

The next day I’m not diving due to bad weather conditions. I take the opportunity to cook, catch up on admin, and even make some money with a freelance job assignment. In the late afternoon, I take an auto riksha to Radhanagar Beach for sunset. Once I leave the photo hungry crowd behind and venture off to the eastern end, it’s actually quite peaceful. Back at the hostel, everyone heads out for drinks — of course I join. We hit Something Different with Janak, Asa, Zahra, Nirmikha, and a couple of their dive course buddies for Shisha and laughs. Followed by dinner at Famous Seafood Restaurant: seven naans (cheese + butter), two chicken dishes, three prawn dishes, and a fish curry. A feast for a grand total of 3,870 INR – life is good.

The next day starts early again. At 6.15am we’re already heading out for “Aquarium” and “The Lighthouse” with four fun divers from Hyderabad and one from Austria. On the boat we’re cracking jokes, and under water we’re laughing when a territorial trigger fish comes for two divers and a camera. On the second dive we see a blue-spotted stingray and another huge octopus. Then, as I’m getting back on the boat, someone yells “DOLPHINS!” and everyone leaps off into the water again. And when the boat arrives at the dive shop beach, two long shadows glide below us. I first mistake them for turtles, but they are dugongs: the resident sea cows. Back on land, I shower and munch on mango, then stroll for another sunset walk. In the evening, the hostel hums with Goldie’s stories: dives at Barren Island, Rajan the swimming elephant, and his log-dragging jungle friends. We almost forget about dinner while listening to the tales of these wild islands.

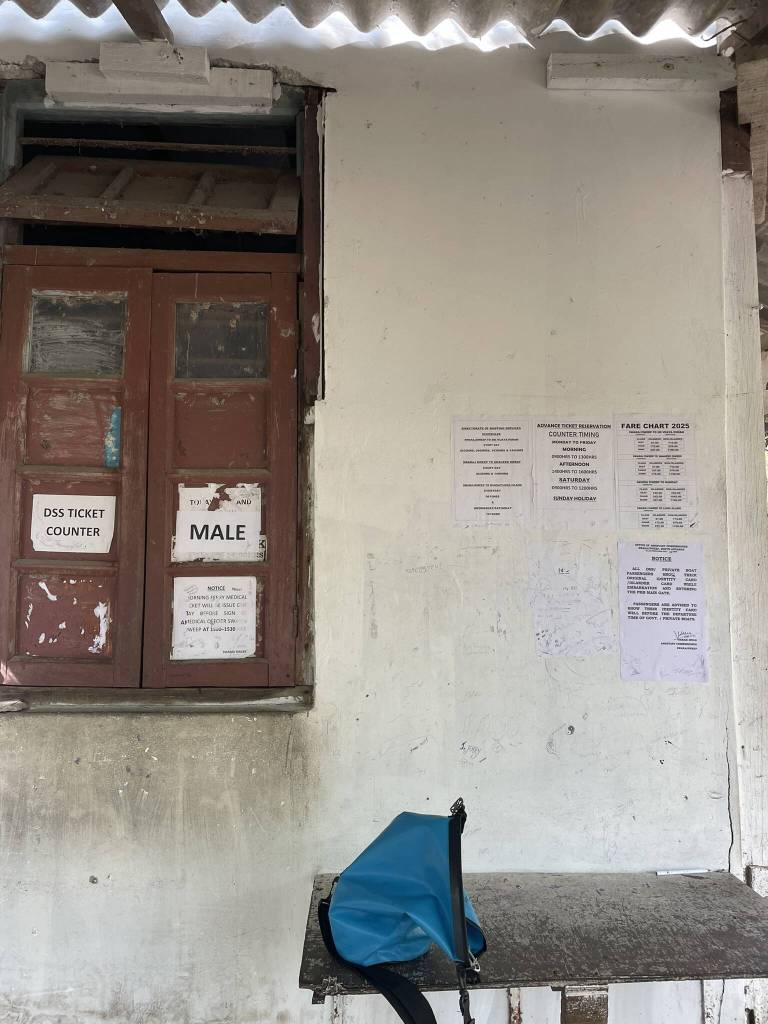

It’s windy. Another break from diving means I can sleep in. After breakfast, I rent a bike and ride to Kala Pathar Beach, stopping along silent coves to read and breathe. The main beach is buzzing with souvenir shops, eateries and lots of tourists enjoying the long weekend. I grab some Maggi for lunch and pedal back to the hostel for a chill afternoon catching up with friends. In the evening, we celebrate Zahra’s last on the island and we finally make it to “Felicità” for Shawarma and a huuuge dessert menu. We then walk 2 km to Narra for cocktails that are definitely worth the efforts and remind me of Marylebone back in London. The next morning, Asa and I accompany Zahra to the jetty for her ferry to Port Blair. We accidentally booked her ticket for the wrong date, but the staff let her board anyway. A hopeful sign, since tickets on my departure date are almost sold out.

Later that morning, Asa & I report to Scubalov for another fun dive. Destination depends on weather, but there is a chance for a deep dive! Once we’re on the boat, captains confirm: we’re heading to Dickson’s Pinnacle, a site that’s been on my bucket list. The surface is choppy but manageable, and as soon as we descend and wait on the mooring line for the rest of the crew to get into the water, the underwater spectacle begins: colorful coral, massive fish schools, and seafans swaying. On a bumpy surface interval before the second dive at the same site, we watch a turtle coming up for air every 20 minutes. Samosas and tea help to keep my stomach grounded, but I’m glad to get back into the calmer blue. The scenes unfolding around the rocks way off the coast are truly spectacular. And guess what: on the only other boat at the site that day, there is THE Dickson who discovered the site with his brothers some 20 years ago when free-diving and spearfishing in the area. The rest of the day is chill, since I want to be fresh for my last dives the next day.

The earliest reporting time yet: 5 a.m. Sites: Jackson’s Bar and Johnny’s Gorge (named after Dickson’s brothers). Janak and his friends from the Advanced Open Water course are on the same boat and we have some good laughs. Once in the water, huge schools of fish, barracudas, and stunning corals fill the dives. Everything goes smoothly, except for the end of the first dive, when Karishma accidentally drops my weights. Before taking off to the second site, she casually descends back down to 30 meters to retrieve them like it’s nothing. On the ride to Johnny’s Gorge, we enjoy vada and tea. Then we’re back in the blue, swimming among even more barracudas and through the deep gorge. I stay present, soaking up every last minute underwater, knowing it would be a while before I return. That night, Janak joins me for my last dinner at the dosa place. Then we watch his Spiti documentary, which stirs a deep longing for mountains and strengths my vision to return to India soon, to visit the far north.

The next day, at 4:45 a.m., an auto riksha takes me to the jetty. Officers give me a bit of a hard time since I don’t have a ticket, but I brushed it off. After all I’ve been trying to buy one for multiple days, but the inconsistent counter opening hours weren’t my fault. Anyway, at 5:30 a.m., I finally board and sleep lightly on the three-hour ride to Port Blair via Neil Island. Once there, I made a spontaneous stop at the Zonal Anthropological Museum and learn more than I expected about the indigenous peoples of these remarkable islands (I included a brief summary at the very end). I leave, already planning to come back — for more dives, explorations and hopefully a dive trip out to the volcanic Barren Island next time. *I know I just said I wanted to come back to India to visit the far north, but please don’t make me choose between mountains and the sea. After all, one of the many things I love about this huge country is its diversity and that I can have both 😉

The people of the Andamans: A melting pot of cultures

While diving in the Andaman Islands, it’s impossible not to think about the layers of human history that exist alongside the reefs and shipwrecks below the surface. The islands may feel remote today, but their population is the result of centuries of movement, coercion, and adaptation—much of it shaped by British colonial rule.

During the colonial period, the British brought people from across the Indian mainland and Burma (Myanmar) to the Andamans, often as convicts or laborers. Bengalis, Tamils, Telugus, Malayalis, Moplah Muslims from Malabar, and others arrived under penal transportation or to work on plantations, infrastructure, and administration. Even some Burmese communities were relocated from neigbouring Myanmar between the early 1900s and the 1920s. Over time, these groups—despite vastly different origins—formed what are now considered the island’s “local” communities, cutting across caste and religion, united more by shared island life than by ancestry.

Alongside these settler communities are the indigenous tribes of the Andaman Islands, whose presence predates colonial history by thousands of years. The Great Andamanese, once spread across much of the archipelago, are now reduced to a small population. The Jarawa for example continue to live along the western coasts of South and Middle Andaman, maintaining a hunting-and-gathering lifestyle deeply tied to land and sea. And possibly the most famous inhabitants of the islands are the Sentinelese, who remain entirely isolated on North Sentinel Island. They avoid contact with the outside world, actively protect their territory and stand as one of the last uncontacted peoples on the planet.

Further south, in the Nicobar group of islands, the cultural landscape shifts again. The Nicobarese tribes, especially the Chowra Islanders, rely heavily on inter-island barter systems rather than cash economies. Chowra is known for its pottery, which is traditionally exchanged for food, tools, cloth, and other essentials with neighboring islands. The Shompen, more isolated and forest-dwelling, practice horticulture and fishing, using trade to supplement what they cannot produce themselves. Canoes and outriggers are central to this exchange network, enabling movement and connection across the sea.